by Bruce Sylvester

Red Hill and White Shell, 1938, Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887–1986), Oil on canvas

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Gift of Isabel B. Wilson in memory of her mother, Alice Pratt Brown.

© 2024 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Jud Haggard.

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Simply and matter-of-factly titled Georgia O’Keeffe and Henry Moore, the Museum of Fine Arts‘ new show is said to be first ever whose theme is bringing together these two 20th-century leaders in fusing nature and abstract mondernism: Moore mainly through sculpture and O‘Keeffe mainly through painting, though we do also see the first of only three sculptures she ever did during her lengthy professional career. The show‘s 150 objects are heavily grounded on found objects like shells, stones and animal bones, Moore’s from his 70-acre farm in the English countryside and O’Keeffe’s from her walks around the wide open spaces of her adoptive home beneath the expansive skies of New Mexico.

O’Keeffe was a master of careful staging to create illusions of size and space. Her much celebrated flowers were often larger in her paintings than in real life because she wanted us to see them more clearly. She’d put a small object in front of a distant background of wide open sky to make the object seem larger. Suspending a deer pelvis midair beneath a faraway sky was a masterstroke.

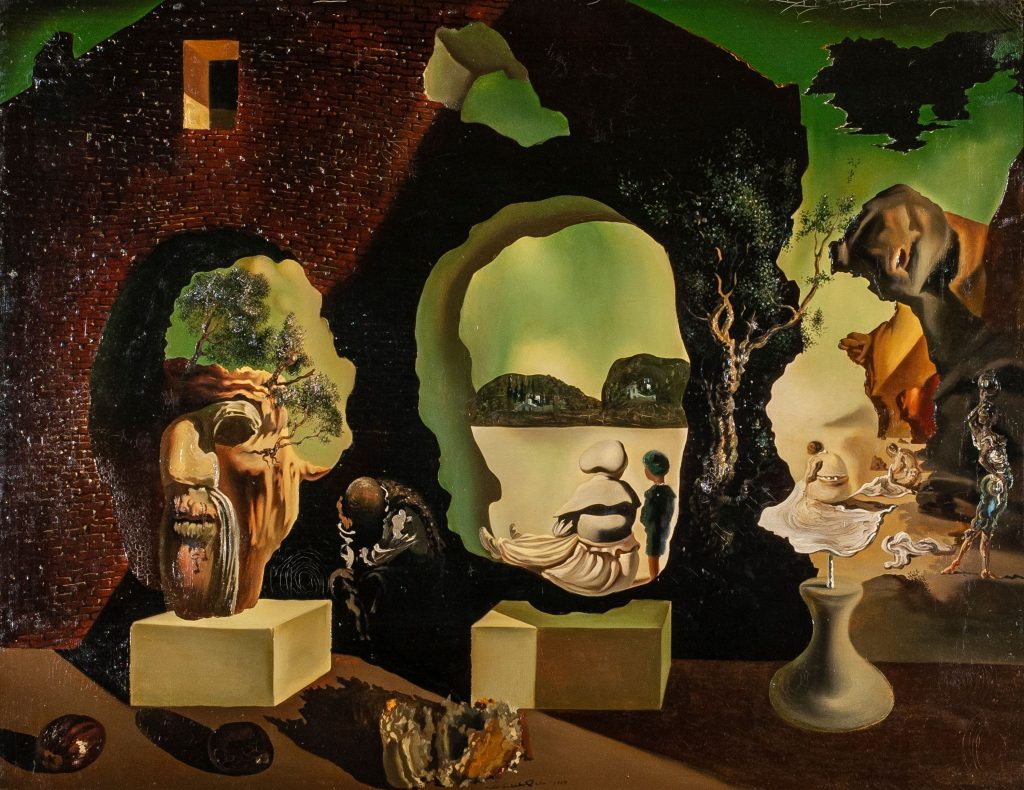

They embraced both the symmetry and the unpredictability of nature. The holes they showed were important to their art. Take the holes in the elm tree section Moore fashioned into a statue of a reclining human. As the show’s excellent wall notes point out, “Gaps and apertures provided new ways of seeing objects and their surroundings. By looking through, new compositional opportunities arose. After all, a hole, Moore remarked, was ‘a shape in its own right, the solid body was encroached upon, eaten into, and sometimes the form was only the shell holding the hole.’ … Moore carefully considered what a visitor would see through the spaces in between sections and how his work could shape that perception.” O’Keeffe once said, “I like empty spaces. … Holes can be very expressive.”

Of course, Stonehenge fascinated Moore. Here are two lithographs of the enigmatic ancient edifice he did when he was 75 years old.

Reclining Figure, 1959‑1964, Henry Moore (English, 1898–1986), Elmwood

The Henry Moore Foundation: gift of Irina Moore 1977 LH 452

Photo credit: Jonty Wilde

Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

We can enjoy recreations of their studios. Some authentic items come from Moore’s. Hers is immaculate and carefully arranged. His is obviously a workplace in the throes of creativity. To enhance our connection with Moore, the MFA has put white splotches on the floor where we’re standing as we perhaps note the similar white splotches on the reproduction of his floor. We see a film of Moore at work. O’Keeffe didn’t allow such films to be made. A photo of him is obviously informal. Her photo looks like she planned and arranged everything about it. Controlling her image was important to her.

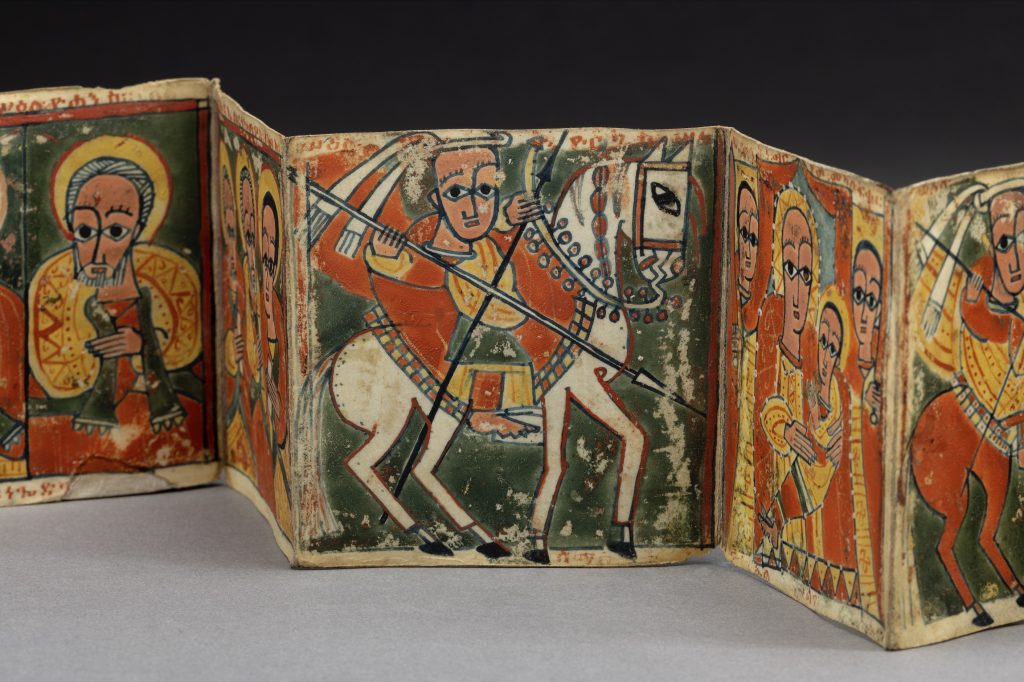

To enhance the show’s context, there are a few items from their modernist contemporaries such as Edward Weston, his son Brett Weston, and Imogen Cunningham. The impressive balancing in a small Alexander Calder sculpture made from four pieces of walnut may reflect his academic background in civil engineering.

A gracefully curving cherry wood bench by Peter M. Adams is both functional and art. In other words, you can sit on it, though the museum asks that we all be careful with it.

The Museum of Fine Arts show Georgia O’Keeffe and Henry Moore is on view through January 20.