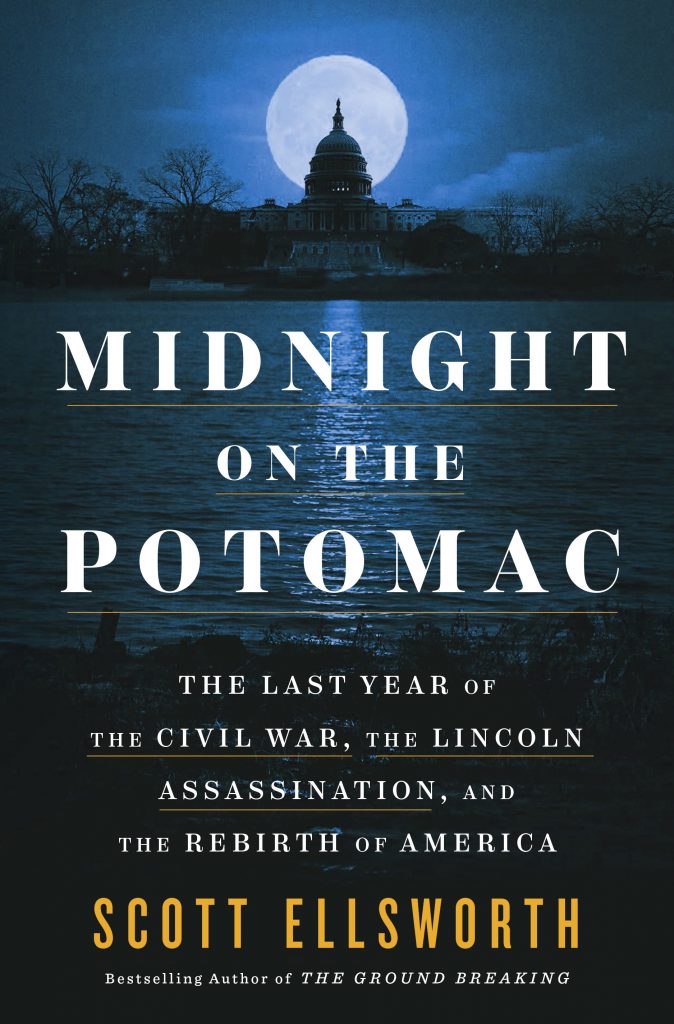

Review: Midnight on the Potomac

By

by Bruce Sylvester / Troubadour, Thursdays 2 – 4 pm

A dark night of the American soul, the Civil War pitted brothers against brothers, states against states. Neither Union nor Confederacy had the full support of its citizens. Some southerners felt that only plantation owners would benefit from secession. As University of Michigan professor Scott Ellsworth writes in his thoroughly researched Midnight on the Potomac: The Last Year of the Civil War, the Lincoln Assassination, and the Rebirth of America (Dutton), “[T]hroughout the Confederacy, there were Union men and women whose voices, though silenced, remained steadfast. In the mountains of North Carolina and in parts of northern Alabama hill country where slavery was practically unknown, Confederate army recruiters had been shot at by the locals. When the state of Mississippi seceded from the Union, Jones County seceded from the state of Mississippi.” As Sherman and his forces marched through Georgia, Blacks escaping slavery joined his army, some becoming valuable spies and scouts since they knew their own region better than the invading Union army could.

The book digs deep into the conflict and its participants, blowing away stereotypes and facile assumptions. Quotes from letters of ordinary citizens are vivid, as are the descriptions of leading figures and others too. A Boston theater critic heaps praise on a performance by future Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth. A concise author, Ellsworth smoothly gets loads of information into relatively few words — for example, the background of self-made woman Laura Keane, the star of the play where theater-loving Lincoln was shot. We also learn of Confederate master spy Thomas Nelson Conrad and his impressive range of disguises.

Well into the war, Lincoln was careless about his own safety until a bullet went through his hat as he rode alone back to the White House one night. Innately conciliatory, he visited both wounded Union troops and rebel prisoners of war on a trip to a military hospital.

Booth (an acclaimed Shakespearean actor) is often assumed to have been the ringleader of the extended plot to assassinate various government officials — perhaps in part because he was the only one of the designated killers to get his mark. But not so. The Confederate Secret Service, which reached up into Canada, planned it. As an actor, Booth was hugely popular in Boston, but a fifth 1864 visit to this city — this one unexplained — seems to have been for a meeting with four other Secret Service men at the Parker House. The original plot was to kidnap Lincoln and ransom him for Confederate prisoners of war. The surrender of the South the next spring led to a change of goals.

Booth — the son and younger brother of noted actors who were anti-slavery — may be the most intriguing character of all here. Matinee-idol handsome, he was genuinely friendly to people of any station and political persuasion. He loved children so much that when young Tad Lincoln asked to meet him, he gave the boy roses regardless of a consuming hatred of his father.

As Ellsworth writes of the stage tragedian who then created his own tragedy to go down in history, “[N]ot only was Booth a remarkable Shakespearean — one whose portrayal of the mad king in Richard III thrilled a generation of playgoers — but his own life was a tragedy all its own. Blinded by racism, manipulated by others, and obsessed with anger and hatred, he not only murdered a great leader but, at age 26, threw away his own life as well. It’s a story that Shakespeare would well have understood.”

Comments closed

Categories: Review

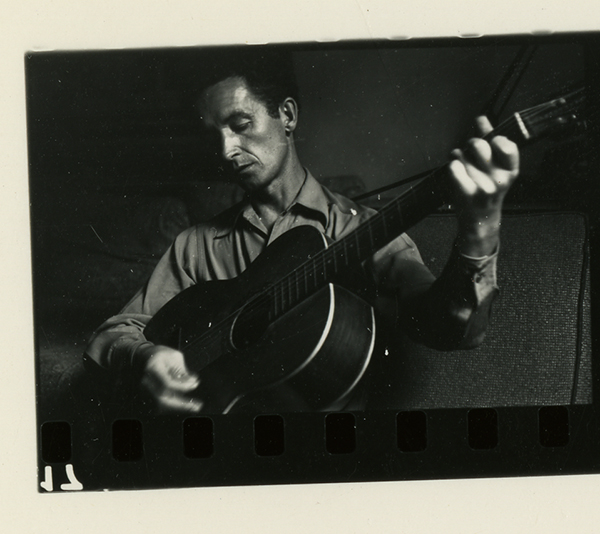

Newly released home tapes by Woody Guthrie are revealing

By

by Bruce Sylvester / Troubadour, Thursdays 2 – 4 pm

A populist poet laureate for America past and present, Oklahoma native Woody Guthrie (1912-67) was progressively deteriorating from hereditary Huntington‘s chorea in 1950 when his publisher, Howie Richmond of TRO Essex, gave him a just-introduced two-track home tape recorder for his new songs, revisions of older ones, philosophizing, and personal messages.

Over 1951 and 1952, prolific Woodrow Wilson Guthrie sent Richmond 32 tapes with over 300 cuts done in his Brooklyn living room. Seven decades later, new Woody at Home, Volumes 1 and 2 (Shamus) shares 22 of them with us. Thirteen compositions are on no other disc. Regardless of countless covers of freshly timely Deportee over the decades, here is the only rendition that Woody himself ever recorded. It has verses I had never heard on its covers.

He believed that no song was ever finished. His were constantly evolving. This Land Is Your Land has lines found nowhere else. Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done (a look at heroism of ordinary people down through history) has lines I had never encountered before. My Id and My Ego shows his playful eroticism. Spoken-word Einstein Theme Song imagines a humanitarian talk with the genius as they rode the rails – a prime means of Depression Era travel when early Guthrie songs were birthed.

The intimate feeling of these informal home recordings is astounding. As is the audio quality, a major accomplishment. Besides lyrics, the booklet accompanying the disc details the remastering proesss. Steve Rosenthal, Jessica Thompson, and Sean McClowry write in Notes on the Transfer and Restoration Process:

Woody Guthrie’s original tapes were made in his home using a consumer tape recorder that played and recorded at a very slow speed, 3 3/4 inches per second. To restore as much fidelity and character as possible in a way that matched the tenor and spirit of Woody’s songs, several combinations of tape heads and settings were researched.

After testing the tapes on multiple reel-to-reel tape machines, the best sonic match was a fully -restored Ampex 350 Tape Recorder from the same years that Woody’s tapes were first recorded. The Ampex 350 was introduced in 1950 and quickly became one of the most important early professional tape recorders of its era. Ampex, one of the original technology companies located in what would become Silicon Valley in California, made professional audio recorders that used vacuum tubes and large, heavy transports. To transfer the Woody tapes, a fully restored Ampex 350 Tape Recorder was played through a Mytek Brooklyn Analog to Digital Converter and recorded at 24 bit/192kz into Avid Pro Tools, where we could take advantage of digital editing and restoration software while staying true to the original sonic character heard uniquely on the original tapes.

Mastering tools primarily consisted of two pieces of software developed using technology with deeply sophisticated algorithmic processing. A stem separation tool to “unmix” the sounds into their own stems, or tracks, which allowed a rebalance of the guitar and vocals. (Woody was not a recordist, and these were not studio recordings, so sometimes his vocals drowned out his guitar strumming.). Another tool was used that neatly pulled out most of the 60-cycle hum that washed over the original recordings and separated it into its own “bass” stem. Woody’s recordings are mono, and they truly capture a moment in time. However, those moments were buried under the detritus of having been recorded onto a slow speed quarter-inch analog tape over 70 years ago. With the worst “noise” out of the way, and the guitars and vocals better balanced, a gain was used to sculpt and refine the recording. A spectral editor further helped attenuate a single fundamental from an overzealous guitar pluck, or tuck in a vocal that came out a bit too exuberantly. Very little equalization or compression was used.

One minor warning: the CD booklet may be hard from some people to read due to print size. Aside from that, the package is phenomenal.

Comments closed